Masjid Shaheed Gunj And Historical Conflict

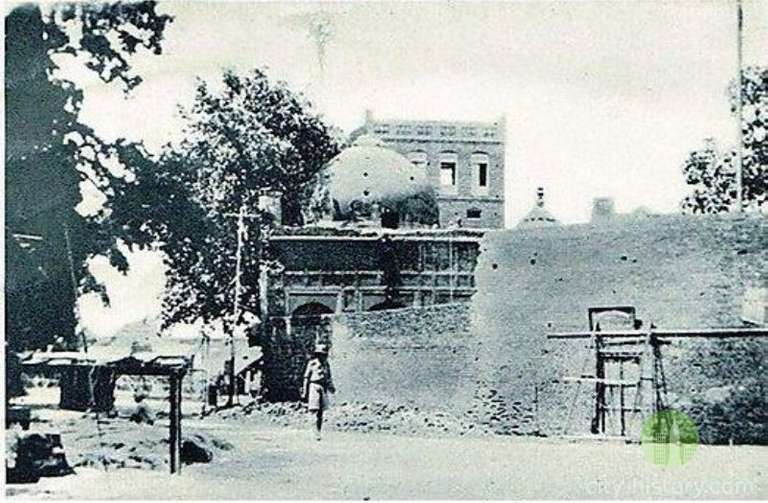

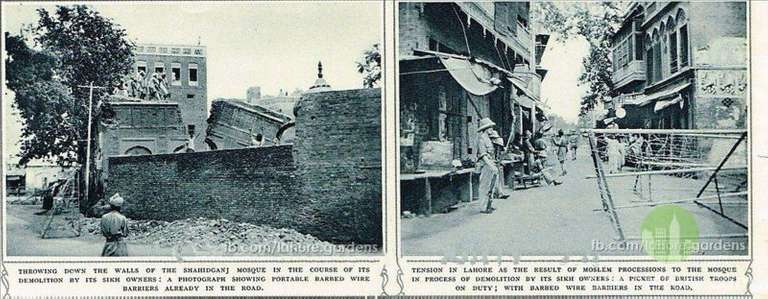

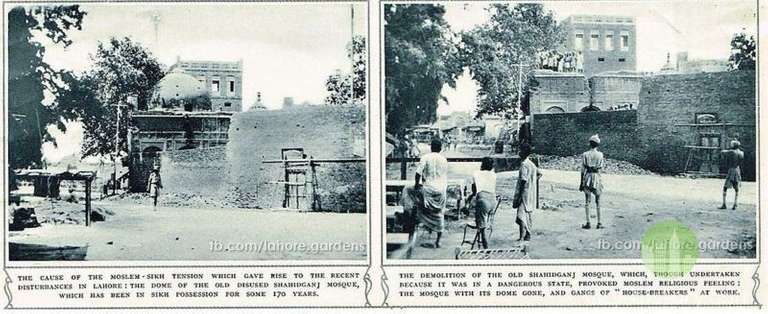

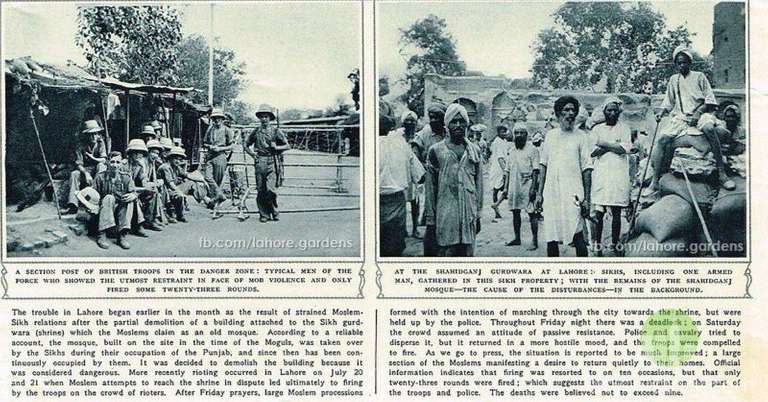

Before 1935 there had stood a beautiful mosque for many years to the south of what is now called the Naulakha Bazaar, in the city of Lahore, having three domes and five arches (as seen in this painting), which had been built as a mosque (masjid) and which retained, notwithstanding consi derable disrepair, sufficient of its original character to suggest, or even to proclaim, its original purpose. It had a projecting niche (mehrab in the centre of the west wall such as is used in mosques as the place from which the imam leads the prayers. Its dedication is no longer in dispute, having been established as of the year A. H. 1134. or A.D. 1722, by the production and proof of a deed of dedication executed by one Falak Beg Khan created a wakf (trust) and dedicated land to build a mosque, appointed Sheikh Din Mohammed and his descendants as muttawalis (trustees) of the mosque, a school and an orchard and a well on the land. All three courts, however, also held - and rightly so - that by adverse possession to Sikhs after 1762 Muslims had lost title to the site and the mosque. By this deed, Sheikh Din Mohammad and his descendants we re appointed muttawalis." The trust deed existed and was on record. The Shahidganj communal issue led to a series of violent riots, which greatly disturbed the Sikh-Muslim population of the Punjab, during 1935-36. For Muslims, the paramount cause of the Shahidganj issue was the protection and possession of the mosque as a prominent symbol of Islamic solidarity. For the events of those times - and the injection of politics in the case - one must turn to K. L. Gauba's narrative "The Shahidganj Case" in his book Famous & Historic Trials (Lion Press; Lahore, 1946; pp. 77-118). For the Sikh view point, vide G anda Singh's History of Gurdwara Shahidganj; Lahore, 1935. "On July 2, 1935, shortly after Sikhs acquired legal possession, a deputation of Muslim leaders met Deputy Commissioner S. Partap who assured them that the mosque would not be demolished. Sikh and Muslim leaders met on July 4 to hammer out an accord. "Muslims were represented by Maulana Zafar Ali Khan, Editor of the Zamindar, Syed Habib, Editor of the Siyasat, Maulana Daud Ghaznavi on behalf of the Ahrars and K.S. Amirud-Din , a local grandee. For the Sikhs attended Master Tara Singh, leader of his community, Sardar Ishar Singh Majhail, Giani Gurmukh Singh and Sardar Mangal Singh, member of the Central Legislative Assembly. The meeting was pursued (sic.) in a most cordial at mosphere and Muslims were asked to put their demands in writing to be forwarded to the Sikh leaders for consideration. The meeting terminated in a hopeful atmosphere. In the evening, Muslims met at the Barkat Ali Islamia Hall under the chairmanship of a Barrister, Mian Abdul Aziz, to formulate their demands. These were specified as the restoration of the mosque to the Muslims and a five-foot passage between the Gurdwara and the Mosque." On July 6, the Governor of Punjab, Sir Herbert Emerson met Sikh and Muslim leaders. The government issued a press note denying rumours of demolition of "the walls of Shahidganj Mosque". The press note appeared in the newspapers of Sunday, July 7. By the next morning the mosque was demolished. The demolition of the mosque was widely condemned. Sir Girja Shankar Bajpai wrote in disgust to Sir Fazl-i-Husain on July 29, 1935 in terms which proved prophetic. "It bodes ill for the future if one community thinks that the best way to assert its legal rights is to wound deeply the religious susceptibilities of another" (Waheed Ahmad (Ed.); Letters of Mian Fazl-i-Husain; Research Society of Pakistan, University of Punjab, Lahore, 1976; p. 420). Together, the Letters and the Diary and Notes o f Mian Fazl-i-Husain (Waheed Ahmad (Ed.); R.S.P., Lahore, 1977) reflect Fazl-i-Husain's deep disapproval of the tactics of extremist Muslim leaders and his efforts for a compromise. They bear on contemporary events. A Diary entry of July 17, 1935 records (p. 150): "It seems to me that H.E. (the Governor) wanted some sort of settlement - the building will remain as an archaeological monument, and not put to any use by Sikhs, and Muslims will not claim it to serve as a mosque. This would have been status quo, and fair. The Muslims however pressed their claim or their request for the building to be used as a mosque, and the Sikhs pulled it down to put an end to the controversy. The Government, feeling possibly that the building will not be pulled down, used its powers against Muslim crowds, and to strengthen the Sikhs, allowed their Jathas to come into Lahore. Sikh Jathas demonstrating in Lahore, and Muslims not allowed to have a procession, naturally created indignation in Muslim circles. Govt. is helping Sikhs to demolish mosque. Well, Sikhs actually demolished it, warned Govt. that they were doing it, and Government could not but protect them with the help of the Police and the Military. This was not playing the game, so far as the Muslim side is concerned, but the Government's explanation is that the Sikhs have acted unfairly." July 19: "What should be done? Deal with Muslim defiance of law and bring it under control. If Sikhs want to build, do not allow it. If they resort to defiance of law, deal with it strongly; as in the case of Muslims. Then the two communities might settle down as quits. It is very unlikely that the Sikhs would agree not to build on it, or in the alternative, out of spite put it to uses which will cause annoyance to Muslims." In the last week of February 1936, Jinnah visited Lahore. Sir Fazl-i recorded on February 27: "Government of India seems to have accepted Jinnah's offer to help, and asked the Governor to co-operate with him. This is all to the good. This trouble stands in the way of the communities coming together, and we should all be grateful to Jinnah for making the effort, and if he succeeds, Punjab benefits from it. Jinnah set up a conciliation board composed of representatives of all the communities. He was not out to exploit the crisis for political ends. Sir Fazl-i-Husain became impatient with Jinnah as an entry of March 8 reveals: "...the site should not be buil t upon, and... its use by the Sikhs guarded against. This was almost promised, and yet violated, if Jinnah is right. This is adding insult to injury and Jinnah still goes on talking of settlement honourable to both" (p. 204). On June 13, 1936 Fazl-i-Husain wrote to the Governor expressing his opposition to any construction on the site of the demolished mosque (Letters; p.584). By then, Muslims had lost the case. In a considered judgment, on May 25, 1936, S. L. Sale, District Judge at Lahore, dismissed the suit which Muslims had filed after the demolition. On November 29, 1937 the High Court began hearing the appeal from the District Judge's judgment. Barkat Ali approached Jinnah, who was still in active practice in the Bombay High Court, to appear for the Muslims. "But he declined because he had been a conciliator between the contending parties in February 1936 and did not want to be an advocate of one party" (M. Rafique Afzal; Malik Barkat Ali, His Life and Writings; R.S.P., Lahore, 1969; p. 44). On Jinnah's advice, F. J. Coltman, an English barrister practising in the Bombay High Court, was briefed. He joined Barkat Ali and Dr. M. Alam for the appellants. Rai Bahadur Badridas and Sardar Harnam Singh appeared for the SGPC. On January 26, 1938, the High Court dismissed the appeal (Masjid Shahid Ganj vs SGPC AIR 1938 Lahore 369). On May 2, 1940, the Privy Council brought the curtain down on the litigation by dismissing the appeal. By then the SGPC had secured in August 1935 the municipality's sanction for construction of a gurdwara on the site of the mosque.

Masjid Shaheed Gunj c. 1935

Comments